The Northwest Sands Story

Welcome to the Northwest Sands Auto Trail, an opportunity to explore the history, geology, ecology, culture and recreational features of one of Wisconsin’s most compelling yet least appreciated landscapes.

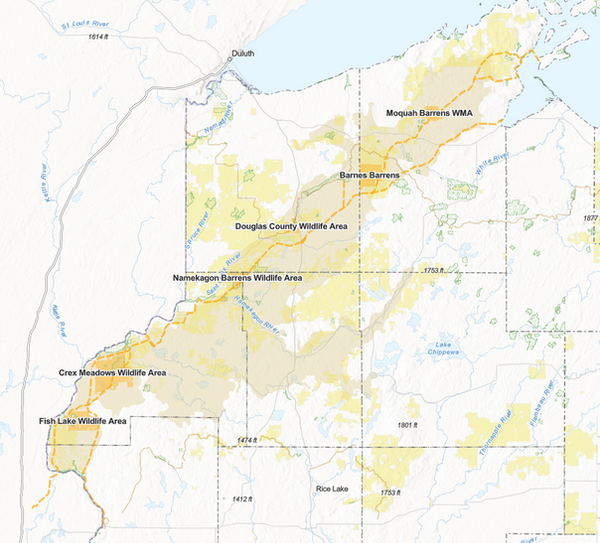

The Northwest Sands of Wisconsin are a belt of deep sand that stretches almost 140 miles from St. Croix Falls to Bayfield. They consist of an unfathomable amount of material washed from glaciers more than 11,000 years ago. This 15-mile-wide deposit of sand has been the dealmaker for this part of Wisconsin. It resulted in dry and open terrain and a globally rare ecosystem of plants and animals. That in turn created a travel conduit between Lake Superior and the Mississippi River region used by generations of indigenous people, white explorers, fur traders, loggers, mail carriers, settlers and tourists. This Auto Trail roughly follows the route of that historical trail – shown on the accompanying map as a red dotted line based on original surveys and other historical records. Many of these people trod and rode the trail countless times.

The sand drains water rapidly and builds soil slowly, so this has been the most fire-prone piece of the state for thousands of years. Fires became even more frequent and destructive for a time, after white settlement took hold and loggers worked pine forests nearby.

While today there are large swaths of second- and third-growth pine forests, there are also areas of open barrens habitat. Scrub oak and jack pine dominate these barrens, and sharp-tailed grouse find one of their largest remaining habitats in Wisconsin. Grasses and prairie flowers like the brilliant orange wood lily differentiate these barrens from those in other parts of the country.

These barrens line up in a southwest-northeast slant across northwestern Wisconsin and they have much in common – shrubs like scrub oaks, hazelnuts, sand cherries, and blueberries; grasses like big blue stem, little blue stem, June grass, Kalm's brome; and forbs like goldenrods, sky blue aster, pussytoes, blazing star, daisy fleabane, puccoon, harebell, frostweed, bergamot, milkwort.

But they differ as well. The land tends to be hillier in the north, where glacial action was different. Bearberry and beach heather are more common in the north, for example, while in the south there are more flowers because of converging prairie, broadleaf forests and dry pine woodlands. Management – use of fire, chemicals, clearing and cutting, for example – also varies among the barrens habitat areas.

For generations, indigenous people have fished and hunted and gathered berries, wild rice and other plants, and walked the open terrain. Long before white people arrived, Native Americans were moving goods, communicating for social and political reasons and making seasonal rounds for hunting and gathering along the terrain between Lake Superior and the Mississippi River region. Yes, they used the fabled water route – back and forth on the Brule and St. Croix rivers. But for much of the year, when rivers were high or low or frozen, walking the trails through the open terrain of the sands would have been easier.

From the 1600s into the 1800s, Dakota and Ojibwe people became key players in the French fur trade in this region. This was a time of mixing – Dakota married Ojibwe people and French fur traders joined with Native Americans to generate a mixed-blood people known as Metis. For a time Dakota and Ojibwe people were allies in the fur trade, but then around 1730, competition for land and furs led to fierce fighting. There were also scourges of measles, smallpox and other diseases that reduced Native American populations. By the 1830s, when Henry Schoolcraft and others explored the rivers and the walking trails, they were inoculating Ojibwe people against smallpox.

The route became known by many names – the “carte de grande chamais,” or “grand footpath,” or, depending on which way you were going, the “Bayfield Trail” or the “St. Croix Trail.” An 1837 map by explorer Joseph Nicollet shows the trail, and mail carriers were soon using it from the falls on the St. Croix to La Pointe on Lake Superior.

Ojibwe leaders ceded most of the Northwest Sands to the U.S. government by means of treaties in 1837 and 1842. They did not relinquish their rights to stay on the land. But when the federal government forced Ojibwe people in 1850 to travel to Sandy Lake in Minnesota Territory to collect payments that the treaties called for, long delays and fierce weather combined to kill hundreds of people. The event today is known as the Sandy Lake Tragedy. Ultimately, the government reversed course and carved a number of northern Wisconsin Ojibwe reservations from the ceded land.

Two notable Ojibwe delegations walked the historic trail on their way to or from Washington, D.C. In 1852 leaders fought the effort to remove the Ojibwe from Wisconsin, walking the trail on their return home. In 1863 a number of chiefs visited President Abraham Lincoln to press for promised payments, walking the trail both ways from Bayfield to St. Paul.

By 1857, the trail was passable for wagons. It was used by dogsleds in winter, and in 1859 a stagecoach used it to start carrying people to the new town of Bayfield. This improved connection between Lake Superior and the Mississippi River region was a key link in the nation’s westward expansion, making news in New York and Washington, D.C. Stopping places were established along the road, offering shelter and food for travelers. Ruts from this stagecoach road are still visible. In some places, the Auto Trail takes the actual stagecoach route. Ultimately, the road fell into disuse in the 1880s as railroads re-shaped how people and goods moved through this part of Wisconsin.

Once the logging boom started to subside in the 1890s, the open land enticed immigrants and other settlers. Farmers carved out livings and created hardy communities, but within just a few decades, many were left windblown, burned out and disappointed when the nutrients were quickly depleted.

Twice in recent decades there have been reminders of how fire-related this landscape is. The Five-Mile Tower fire in 1977 and the Germann Road fire in 2013 each burned thousands of acres in just a day or two, destroying dozens of residences and other structures.

Today, the sands are a mix of private and public lands, much of it shaped by revenue-producing forestry, by tourism and by seasonal residents.

But habitat conservationists and a collection of local, state and federal agencies are managing the corridor of open areas to maintain features present on the land for centuries.

In the Sterling Barrens and Fish Lake Wildlife Area in the south, Crex Meadows in the southwest, Namekagon Barrens and Douglas County wildlife areas in the middle and Barnes Barrens, Bass Lake Barrens and Moquah Barrens in the northeast, wildlife managers conduct controlled burns and take other steps to maintain a “mosaic” of habitats in the globally endangered ecosystem. Several “Friends” organizations volunteer and raise money to help.

This Auto Trail is your guide to the Northwest Sands, an effort to help you appreciate the significance, beauty and history of a fascinating area. You can take the tour in your arm chair if you want, exploring the interactive map, reading the short summaries of dozens of sites with historic or natural significance, clicking on photos and finding further web links. Or you can use the guide to take you on a multi-day, backroads course in the natural and human history of a fascinating part of Northwestern Wisconsin.

You can still find the old Stagecoach Road, for example. You can walk around well-kept old cemeteries and a school foundation marking the lives of struggling farm families from 100 years ago. The route includes places where Ojibwe people have lived, hunted and picked berries for hundreds of years, sometimes using fire to manage the land. You can kick the sand that glaciers deposited, see the “kettle lakes” formed where blocks of ice melted and gaze into the massive St. Croix River spillway carved by glacial floodwaters. You can see how a shifting habitat might be home in one place to sharp-tailed grouse or upland plovers and in another to Kirtland’s warblers.

We start on the southern end of the route but feel free to dive in anywhere. Travel for a few minutes or for days, exploring the history and the ecosystem.

The route of the Northwest Sands Auto Trail is over 200 miles long, following the old historical trail where it can. But it detours here and there, sometimes because it must and sometimes just to get close to another point of interest. It has a starting point and an ending point because it has to, but you can pick it up anywhere and follow it in either direction as far as you want.

And remember it’s all because of the sands.